Many countries have pledged to achieve net zero emissions anytime between 2035 and 2070, with India aiming for 2070. Net zero, first formalised in 2009 according to the United Nations, refers to reducing carbon emissions to a small residual amount that can be absorbed and durably stored by nature and other carbon removal measures, leaving nothing additional in the atmosphere.

“Net zero is not just an abstract climate target; it’s an economic and strategic agenda,” said Hisham Mundol, chief advisor, India, to the Environmental Defense Fund. “Expanding renewables can cut dependence on imported fuels, reduce local air pollution, and lower the climate risks already affecting millions of farmers.”

X – X = 0: mathematically possible, environmentally impossible?

Yet, critics warn that the promise of net zero often masks harsh realities. Many assume it implies a fossil fuel-free future, but climate activists argue it can instead serve as a loophole — allowing governments and corporations to continue burning fossil fuels while pledging to offset emissions later.

This concern is reinforced by the Global Climate and Health Alliance’s latest report Cradle to Grave: The Health Toll of Fossil Fuels and the Imperative for a Just Transition, which notes that despite overwhelming scientific evidence and economic risks, including stranded assets, new fossil projects still receive approval.

IIT Bombay professor and solar scientist Chetan Singh Solanki likens net zero to a mathematical trick: X – X = 0. “This definition hides its environmental impact, as consumption and generation keep rising without limits. Unless you cap consumption itself, net zero has no meaning. That’s why I say net zero cannot be our hero,” he said.

Even renewable technologies, Solanki pointed out, require mining iron, copper, aluminium and other resources. “These must also be recycled later, which consumes more energy. So, net zero may exist mathematically, but environmentally it is always net positive,” said Solanki, who holds a PhD in solar technology.

Racing against time

Solanki also questioned the timeline itself. Global warming of 1.5–2°C is projected within the next two decades, a tipping point he called “ultimate irreversibility”. “If we cross it by 2045 or 2050, then what is the point of targeting net zero by 2070? There is absolutely no point. So, I feel surprised that people don’t talk about the basics fundamentally,” said Solanki.

Story continues below this ad

Climate activist Shailendra Yashwant agreed. “Net zero is little more than a buzzword. It creates the illusion of action while fossil fuels keep expanding. You can’t burn oil now and plant trees later. Offsets and carbon credits are accounting tricks, not real solutions. The atmosphere only responds to actual emission cuts, not distant promises for 2050 or 2070,” he told indianexpress.com.

According to Solanki, the proof is reflected in the last three or four decades, where despite having policies like the Paris Agreement, COP meetings, and having innovations and technology, solar offers cheap and advanced potential, and there are EV, green hydrogen, “our problems are increasing. In fact, it is increasing faster than ever”.

Is Net Zero really achievable environmentally? (Photo: Freepik)

Is Net Zero really achievable environmentally? (Photo: Freepik)

Why should we care?

Carbon dioxide lingers in the atmosphere for 300 years. “Every time you emit it, you must be a thousand times more careful,” Solanki stressed. And the costs are visible everywhere — from wildfires in the Americas to catastrophic floods in India’s Uttarakhand, Punjab, and landslides in Kerala’s Wayanad, and multiple heatwaves, unheard of before.

Story continues below this ad

“Climate change is happening as we speak, and we continue to mull over what can help. Net zero may sound like jargon, but at the end of the day, it’s about your child’s lungs, your parents’ heart health, and your own ability to breathe freely. “It’s not just a climate issue, it’s a daily health issue,” said Dr Manas Mengar, consultant pulmonology, KIMS Hospitals, Thane.

“Heatwaves thicken the blood and raise risks of clots and strokes. Smoggy days damage the lungs as much as smoking several cigarettes. Children breathe faster, so they inhale more pollution. The elderly and people with asthma, diabetes, or hypertension are especially vulnerable. For them, every degree rise in temperature or every spike in pollution can trigger an emergency,” said Dr Mengar.

Net zero or real zero?

As COP30 approaches in Belem, Amazon — the world’s largest carbon sink — activists say the conversation must move from “accounting gimmicks” to real emission cuts, justice-based transitions, and ecosystem protection. “If Belem becomes the COP that shifts governments from net zero to real zero, that will be a breakthrough,” said Shailendra.

Aarti Khosla, founder of Climate Trends, noted that Brazil is working on pathways to make outcomes “real and implementable” despite a difficult geopolitical backdrop. Meanwhile, Ulka Kelkar, climate programme director at WRI India, acknowledged both real zero and net zero are “very difficult,” requiring a fundamental shift in how we produce, build, and travel. “The ethical dilemma with net zero, however, is that it should not leave room for the affluent to maintain unsustainable lifestyles simply by paying for the efforts of others,” Kelkar said.

What’s the solution ahead?

Story continues below this ad

For Solanki, tackling climate change is like treating cancer — you must address the root cause. “Solar, wind, EVs and green hydrogen are like paracetamol. They make us feel better but don’t cure the disease. The real problem is ever-growing consumption on a finite planet. Our cupboards, vehicles and buildings keep increasing. Technology, science, and policy cannot help unless consumption is capped.”

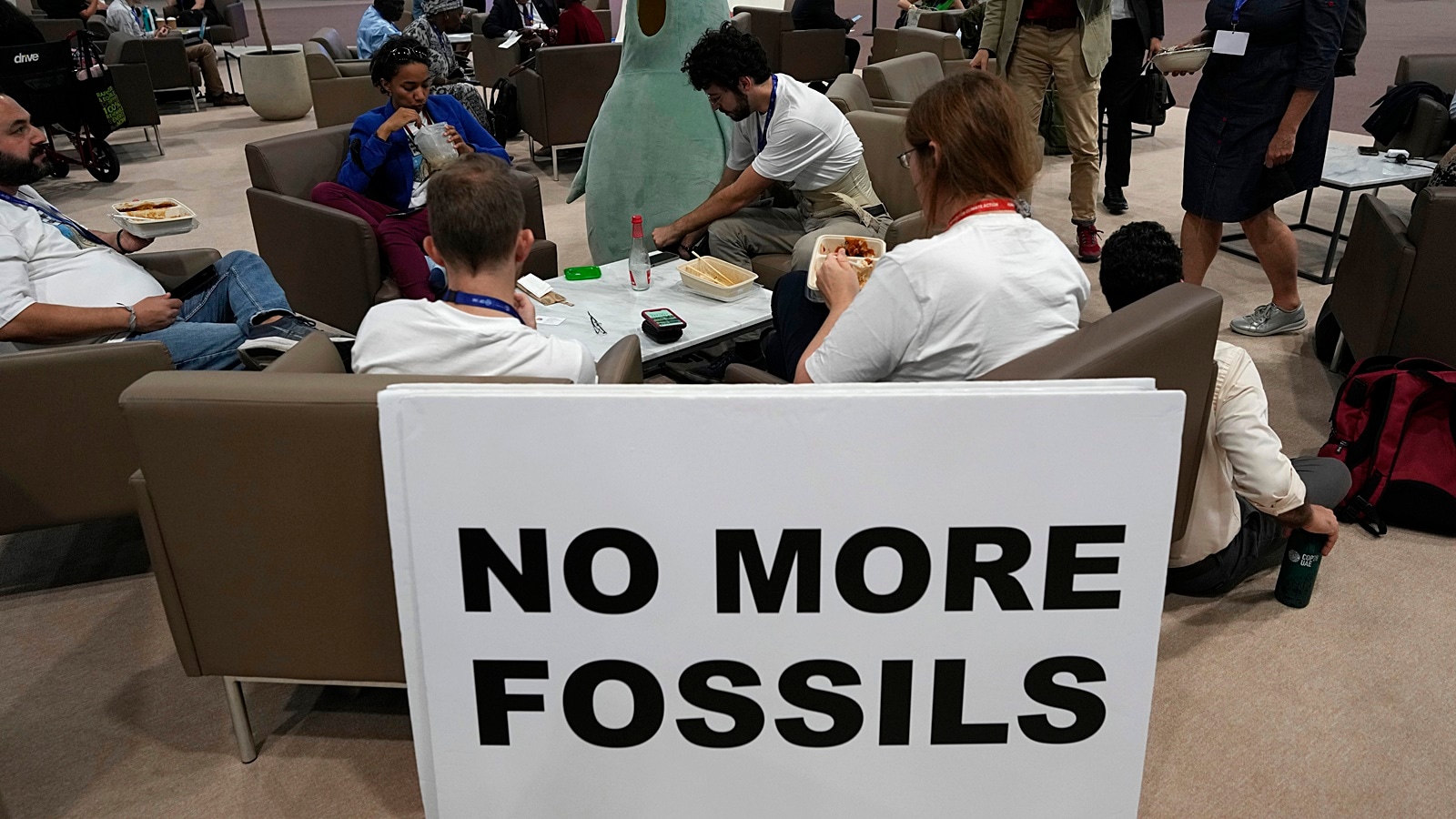

A dugong costume sits while a group eats lunch near a sign reading “no more fossils” at the COP28 UN Climate Summit. (Photo: AP)

A dugong costume sits while a group eats lunch near a sign reading “no more fossils” at the COP28 UN Climate Summit. (Photo: AP)

As part of his “consumption literacy” campaign, Solanki promotes two frameworks:

T is for travelling less

U is for utilising items wisely

P is for purchasing cautiously

E is for eating carefully, reasonably, and seasonally, since 25 per cent of global carbon emissions come from the food industry.

E is for eliminating electricity waste.

There is another approach named AMG, which is a decision filter.

Story continues below this ad

Avoid what is avoidable.

Minimise what you cannot avoid.

Generate locally what you cannot minimise.

“These principles are universal,” Solanki said. “If 8.3 billion people and their institutions followed them, we could make a real difference.”